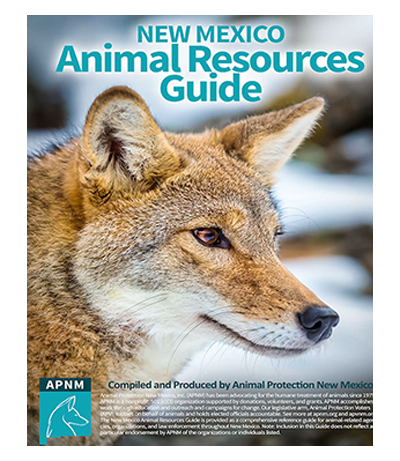

For decades, cougar management in New Mexico has not been based on biological principles; this has resulted in archaic management practices, anti-cougar bias and excessive cougar killing. Animal Protection New Mexico (APNM) has been working since 1996 to change these attitudes and practices that put cougar populations at risk in New Mexico.

For decades, cougar management in New Mexico has not been based on biological principles; this has resulted in archaic management practices, anti-cougar bias and excessive cougar killing. Animal Protection New Mexico (APNM) has been working since 1996 to change these attitudes and practices that put cougar populations at risk in New Mexico.

Due to the public’s and APNM’s advocacy for stronger cougar protection, in August 1998, the New Mexico Game Commission (Commission) adopted a Cougar Management Plan (Plan). The Plan, which included kill quotas and zone management, was the first of its kind in the nation, to our knowledge. While inadequate in some respects, the Plan was a positive step in that, for the first time, it imposed some specific restrictions on cougar killing in New Mexico. Approval of the Plan nullified the Commission’s earlier double-bag limit policy.

Although the Commission-approved double-bag limit was in effect for one season, APNM withdrew its lawsuit against the Commission, a suit that challenged the double-bag limit. This was because the Plan was implemented almost immediately after APNM’s lawsuit was filed, in the summer of 1999. Following is a summary of APNM’s persistent involvement in cougar management in New Mexico.

APNM and Defenders of Wildlife Sue New Mexico Animal Damage Control

In May 1998, APNM and Defenders of Wildlife (Defenders) sought to stop Wildlife Services (formerly Animal Damage Control), the US Forest Service, and the Bureau of Land Management from further cougar killing on federal lands until the defendants comply with the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA). The suit, filed in New Mexico Federal District court, asked that the defendants assess the impacts of their cougar killing in New Mexico by preparing an adequate Environmental Assessment (EA), and if necessary, an Environmental Impact Statement.

Wildlife Services (WS) had published EAs for predator damage management in all three of its state districts. But the assessments “failed to consider significant, relevant and new scientific information about cougars” published in a study by the prestigious Hornocker Wildlife Institute. The $1.4 million, ten-year study was commissioned by the New Mexico Department of Game and Fish (NMDGF) and focused on cougars in the San Andres Mountains. Hornocker’s Ken Logan is clear in stating that no one knows the population size or trend of New Mexico’s cougars. Yet Wildlife Services made dangerous assumptions about cougars without any hard data in their EAs. Study results were misinterpreted and even ignored. ADC essentially shelved the study in favor of maintaining the agency’s status quo of killing cougars without regard to the impact of their killing.

In January 2000, APNM and Defenders of Wildlife prevailed in court when it was determined that ADCs cougar killing violated federal law. The United States District Court for the District of New Mexico held that the federal predator control program violated NEPA by failing to consider important information about cougars published in a report of a ten-year study of cougars in the state. The study was conducted by Ken Logan of the Hornocker Wildlife Institute and has been referred to as the Logan Report.

Specifically, United States District Judge James Parker found: Because Defendants do not have an accurate estimate of the cougar population based on scientific data, because there is no data to support the EA’s assertion that the cougar population is stable, and because Defendants have failed to provide a satisfactory explanation of their utilization of the 28% or 30% sustainable harvest level, it is not possible to know whether the cougar population is actually declining in any of the three districts. If it is, any impact on the cougar population from the predator damage management program-even the deaths of seven to eleven cougars each year-could have a significant impact on the human environment.

Click for full image size

The Court stated that the “Defendants’ conclusion that the predator damage management program will not have any significant effects on the environment appears to be based on assumptions, presumptions, or conclusions themselves not facts based on any evidence, documents, or data in the Administrative Record.”

The Court further pointed out that the “Defendants seemed to have plucked from the Logan report without considering all of the data contained in the report,” illustrating the point that agencies routinely pick and choose whatever science tends to support the status quo of killing wildlife without consequence.

The Court agreed with APNM’s position that ADC did not base its predator damage management of cougars on sound science and remanded the agency’s decisions for further study. While the decision did not affect cougar hunting nor enjoin ADCs killing of cougars in New Mexico, it did require ADC to gather the necessary scientific data and conduct the required scientific analysis to determine whether the predator damage management program will have a significant effect on the human environment.

APNM’s Executive Director Elisabeth Jennings stated, “We hope that federal and state agencies are paying attention to this decision and see it as a wake-up call. If arbitrary agency decisions with the potential to harm wildlife can’t be challenged through the process of public involvement, they will be challenged in the courts. ADC is a particularly egregious agency in that there is no appeals process. Unless you go to court, you get what you get, like it or not.”

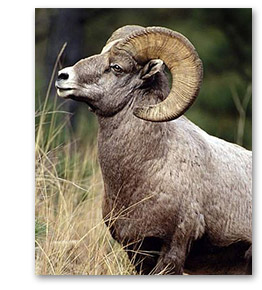

Cougar-Bighorn Sheep Conflict

In the summer of 1999 APNM first learned that the Commission intended to authorize preventive killing of additional cougars, ostensibly to protect the state’s endangered bighorn sheep in four areas. APNM’s research indicated that more likely causes for the decline of the bighorn sheep population were eradication of habitat, loss of preferred cougar prey (mule deer), and human encroachment into bighorn habitat. After all, cougars and bighorn sheep evolved together and have thrived in each other’s presence for centuries. APNM generated widespread media supportive of its position, challenging the targeting of cougars, while other causes of bighorn decline were largely ignored. In addition, plans to do intensive cougar control in bighorn areas have never included meaningful measurements of the effect of such intensive cougar control. (Game and Fish currently claims they are measuring the effect of their cougar control, but when pressed on the issue, they are on record saying that they cannot give a date for which the data they’ve collected will be reduced to reveal any meaningful information about cougars or bighorn sheep.) At Commission meetings, APNM exposed and formally protested the Department of Game and Fish’s (Department) failed plans to increase cougar kills in what amounted to one quarter of the state (15 hunt units) for five years. The Commission voted to continue the killing plans anyway, beginning in September 1999.

In the summer of 1999 APNM first learned that the Commission intended to authorize preventive killing of additional cougars, ostensibly to protect the state’s endangered bighorn sheep in four areas. APNM’s research indicated that more likely causes for the decline of the bighorn sheep population were eradication of habitat, loss of preferred cougar prey (mule deer), and human encroachment into bighorn habitat. After all, cougars and bighorn sheep evolved together and have thrived in each other’s presence for centuries. APNM generated widespread media supportive of its position, challenging the targeting of cougars, while other causes of bighorn decline were largely ignored. In addition, plans to do intensive cougar control in bighorn areas have never included meaningful measurements of the effect of such intensive cougar control. (Game and Fish currently claims they are measuring the effect of their cougar control, but when pressed on the issue, they are on record saying that they cannot give a date for which the data they’ve collected will be reduced to reveal any meaningful information about cougars or bighorn sheep.) At Commission meetings, APNM exposed and formally protested the Department of Game and Fish’s (Department) failed plans to increase cougar kills in what amounted to one quarter of the state (15 hunt units) for five years. The Commission voted to continue the killing plans anyway, beginning in September 1999.

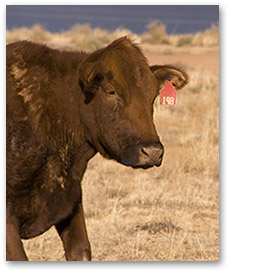

Livestock Depredation Kills

In the spring of 2000, ranchers in southeastern New Mexico asked the Department to expand a controversial cougar killing program known as the GMU (Game Management Unit) 30 Program. The expansion would have authorized additional preventive cougar killing in prime cougar habitat, ostensibly to reduce livestock depredation. The Department abandoned the project at the time, but has just recently revived the flawed plan, which has benefited fewer than six area landowners, at a cost of just under $42,000 per year in payments to a private trapper who is the father of one of the ranch owners.

In the spring of 2000, ranchers in southeastern New Mexico asked the Department to expand a controversial cougar killing program known as the GMU (Game Management Unit) 30 Program. The expansion would have authorized additional preventive cougar killing in prime cougar habitat, ostensibly to reduce livestock depredation. The Department abandoned the project at the time, but has just recently revived the flawed plan, which has benefited fewer than six area landowners, at a cost of just under $42,000 per year in payments to a private trapper who is the father of one of the ranch owners.

Since 1985 in GMU 30, up to 14 cougars could be killed each year, regardless of whether or not livestock losses have actually occurred. The Game Commission recently increased that number to 20, and allowed the preventative program to be unit-wide. NMDGF records show that between 1985 and 1999, 173 cougars were killed in GMU 30 alone in the program. Since 1985, NMDGF has paid over $1/2 million to kill cougars in this controversial program for the benefit of five ranchers in the beginning, and over the lifetime of the program for the benefit of about ten to fifteen ranchers.)

Additional Changes to Cougar Zone Management

In August 2000, the Commission passed cougar hunting regulations (for the 2001-2002 season) expanding the cougar season to a year-round hunt in the bighorn sheep ranges of three management zones. At the September 2001 Commission meeting, the Commission approved the largest ever statewide quota of 227 cougars for the 2002-2003 season; unlimited, year-round cougar hunting and two cougar hunting tags per hunter in all desert bighorn sheep areas and two Rocky Mountain bighorn sheep areas; two hunting tags per hunter for bighorn areas; and year-round, unlimited cougar hunting on private land. Additionally, in February 2002, the Commission voted to allow year-round, unlimited cougar hunting in three game management units in southeastern New Mexico and two cougar licenses per person in those units. The commission also approved an increase from 14 to 20 cougars allowed killed per year in a preventative killing program in GMU 30.

Collectively, these Commission and Department actions indicate a disturbing trend toward completely undermining the Cougar Zone Management Plan which, from the outset, was unscientific and inadequate.

A Statewide Cougar Lawsuit

The Commissions failure to heed the advice and recommendations from a 10-year study (Hornocker Study) of cougars that it funded, and their failure to develop and implement a scientific and effective cougar management plan has forced APNM to challenge its statewide cougar management policies in court. APNM’s suit argues that the Commission is not fulfilling its statutory mandate to maintain an adequate supply of cougars in New Mexico.

In 2006, APNM continued its efforts to ensure a stable and healthy cougar population in New Mexico. APNM paid for the creation of the best available cougar habitat map by GIS experts in the state. Coupled with exhaustive research on cougar management as well as negotiations with New Mexico Department of Game and Fish (NMDGF), APNM made several recommendations to the New Mexico Game Commission (Commission) for improvements to the cougar regulations.

In the meantime, in August and September 2006, APNM teamed up with Sinapu (now WildEarth Guardians)–a Colorado-based conservation group–and made ten public presentations about cougars and New Mexico’s regulations. Events in Taos, Los Alamos, Santa Fe, Albuquerque, Grants, Ruidoso, Las Cruces, and Siver City drew over 300 people and prompted substantial feedback to NMDGF on cougar management.

In September 2006, the Commission voted to reduce the number of cougars that hunters could kill. These changes once again signaled the beginning of better cougar management for New Mexico, even though the approved approach still needed improvement.

Details of regulation changes approved by the commissioners and recommended by APNM included:

- Cougar population estimates were based on habitat mapping specific to cougars–this significant change resulted in a reduction in cougar hunting because population estimates were based on better information;

- NMDGF personnel were expected to evaluate the age and sex of cougars killed in the state as a way to estimate the health of the state’s cougar population–the age of females to be determined by extracting a tooth from every one killed; and

- If the percentage of cougars killed in any unit equaled 20% or more for two years in a row, female sub-limits could be implemented in that unit (APNM requested female sub-limits in certain units where females comprise 20% or more of the kill–that was not approved.)

These 2006 regulations moved cougar management in a better direction, but APNM was still unsatisfied with certain aspects of the regulations: in particular that NMDGF still had two separate cougar kill quotas: one for hunting and one for cougars killed for depredation, on private land, and in areas such as bighorn sheep units. That NMDGF decided–for the first time–to keep track of all cougar kills is commendable, but NMDGF did not maintain separate quotas for any other species. In addition, other cougar biologists were not recommending this approach, and to our knowledge no other state was managing cougars or any other species this way.

The fight for New Mexico’s cougars continues. In 2015, the New Mexico State Game Commission approved the 2016 Bear & Cougar Rule (or “Cougar Rule”), ruling unanimously to allow:

- Cougar trapping using leg-hold traps and snares on state trust lands, totaling 9 million acres in New Mexico

- The removal of the NMDGF permit requirement for landowners to use traps and snares to kill cougars

- One person to kill up to four cougars in the majority of game species management zones, where current unjustifiably high cougar harvest levels are not being met.

Animal Protection New Mexico, along with the Humane Society of the United States and several concerned New Mexicans, filed legal action in state and federal courts challenging the expansion of trapping and mortality of cougars in the Cougar Rule.

In its state case, APNM argues that the Commission failed to consider adequate and reliable science and the indiscriminate nature of traps and snares significantly threatens non-target companion animals, hunting dogs, endangered species, and other protected wildlife. In the federal case, APNM asserts that expanded trapping not only results in cruelty to targeted cougars, but it also poses a clear threat to non-target endangered species like Mexican wolves and jaguars.

APNM’s 5-year Stop Cougar Trapping campaign–which included grassroots action, two lawsuits, and rulemaking advocacy–culminated in a win when the New Mexico Game Commission banned recreational cougar trapping and lowered the annual kill limit for cougars overall. The cougar trapping lawsuit was subsequently dropped.